Continental Warmth

The Schirmacher Oasis is a rare and striking juxtaposition in Antarctica’s frozen world — a 25 km (15.5 mi) ribbon of exposed rock between glaciers, kept ice-free year-round by katabatic winds, low snowfall and intense summer sunlight. This rocky plateau reveals some of the continent’s oldest geology, with formations over 600 million years old from the ancient East Antarctic Shield.

A Geological Anomaly

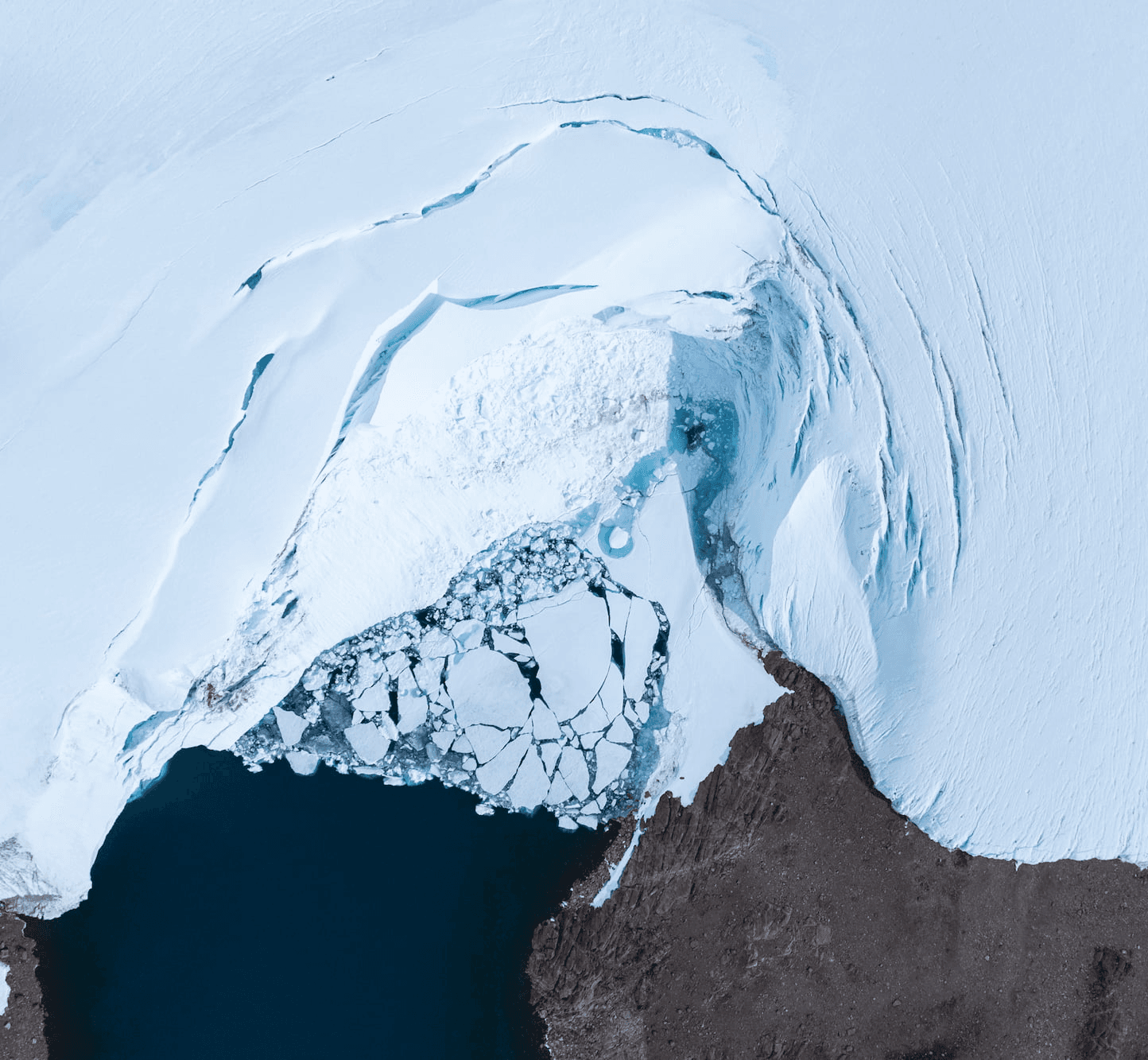

The darker bedrock absorbs more heat than the surrounding ice, allowing the oasis to form its own subtle microclimate — slightly warmer, calmer and more stable than the polar plateau beyond. Set within this distinctive environment are more than a hundred freshwater lakes, melt streams and small glaciers, a rare confluence of ice, rock and water found almost nowhere else on the continent. Among them is Lake Untersee on the eastern fringe of the oasis, one of Antarctica’s deepest and clearest lakes. Its ancient microbial mats are of particular scientific interest, offering a glimpse into ecosystems that may resemble early Earth life. Many of the oasis’s lakes remain ice-covered throughout the year, while summer melt channels carve luminous blue pathways through granite outcrops. Small cirque glaciers feed into the plateau, creating a continual dialogue between ancient bedrock, seasonal meltwater and shifting ice. This unusual hydrology has made the Schirmacher Oasis a focal point for polar limnologists and climate researchers.

Despite Antarctica being the driest desert on Earth, the oasis supports an unexpectedly rich suite of specialised life. Antarctic skuas patrol the rocky terrain; snow petrels and Antarctic petrels nest on cliffs and ridges; and Wilson’s storm petrels, among the world’s smallest seabirds, shelter in crevices and beneath boulders. Even Adélie penguins occasionally wander inland to rest or escape coastal storms.

The ice-free ground also sustains terrestrial species found in only a handful of places on the continent: moss beds that flush bright green at the height of summer; hardy crustose lichens anchored to ancient granite; and microscopic pioneers such as tardigrades, rotifers, nematodes and mites surviving in thin films of moisture. Cyanobacteria flourish in the upper layers of the lakes, forming the foundation of these resilient food webs.

A RIBBON OF EXPOSED ROCK AND SHALLOW LAKES FORMS A DISTINCTIVE PLATEAU THAT HOLDS ITS OWN CHARACTER WITHIN ANTARCTICA’S WIDER EXPANSE OF ICE.

More

about us

Our Story

The story of White Desert is, ultimately, the story of the people who believed it could be done.

Sustainability

The Antarctic Treaty, first signed in 1959 and now joined by 46 countries, lays the foundation for all activity on the continent.

Foundation

By leveraging our unique access to the Antarctic interior, we support researchers studying the planet’s climate and drive initiatives that reduce carbon emissions while restoring fragile ecosystems

Our Camps

At White Desert, each of our camps reveals a different facet of Antarctica’s astonishing beauty.